The MIT Media Lab is located in a classically modern building. At night, its glossy white walls, floors, and ceilings shine through its glass perimeter to cast a futuristic glow onto the surrounding streets.

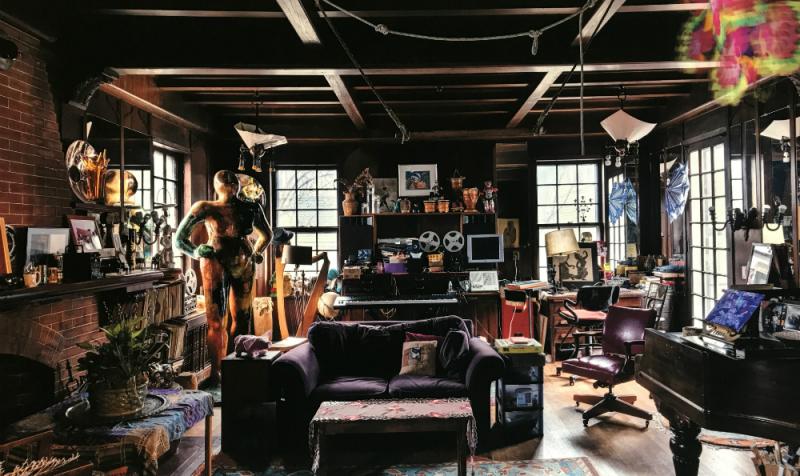

But the part of the building that best reflects the Media Lab’s forward-thinking spirit is actually a picture of the past. Dominating the hallway of the Amherst Street entrance is a towering, three-part portrait showing the eccentric Brookline living room of legendary MIT staffer Marvin Minsky.

Many people consider Minsky, who passed away last year, the father of artificial intelligence. His influence spans from his 1951 invention of the first neural net machine at Harvard to the pioneering work currently being done at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (which Minsky co-founded).

For most of Minsky’s career, however, progress in AI was limited to research papers and experimental, one-off prototypes. Today, the hype surrounding AI’s commercial applications has many people insisting it will be the driver of the next big tech wave, creating systems that aid (or replace) workers in every sector of the economy.

“I think machine intelligence represents a once in a lifetime opportunity for entrepreneurs,” said Vivjan Myrto, Co-Founder of AI-focused VC firm Hyperplane Venture Capital. “It also represents a massive opportunity to invest in technologies that are solving really large-scale problems.”

Boston has long been known for its hard tech contributions, but that hasn’t always translated into the creation of market-leading tech giants. Even more discouragingly, in several cases, some of the city’s most promising startups have moved to California as they’ve scaled.

Rob May, Founder of AI-driven virtual assistant company Talla, believes Boston tech companies have had a more conservative approach to the market in the past, a mindset that has sometimes taken its toll. But May thinks AI’s emergence will play out differently than previous tech waves, and he’s not alone.

In fact, people within the Boston tech community are almost uniformly optimistic that Boston is as well-positioned as anywhere to produce the next great companies built around AI solutions.

A History of Intelligence

The colorful portrait of Minsky’s room serves as a vibrant reminder that the city of Boston is the birthplace of much of humanity’s knowledge of AI.

As progress in the field has quickened, many local and state governments have pledged support for AI research and implementation. But in Boston, AI isn’t the latest fad, it’s a long-standing tech frontier we’ve been involved with since its inception.

“We’ve been doing this since way before it was the next big thing in software, since way before it was cool,” said Catherine Havasi, a longtime member of MIT’s Media Lab who founded text analytics spinoff Luminoso in 2010.

Boston’s experience with AI gives local companies several advantages when developing AI solutions that can actually add value in a business environment, which is more difficult than many people think.

Machine learning techniques, for example, use data to train systems to complete a range of tasks including object recognition and detecting credit card fraud. Although these systems don’t need to be painstakingly programmed for each task, they’re often only as effective as the datasets going into them, thus requiring companies to maintain collections of clean, well-labeled data to optimize a system’s performance.

Deep learning, a subset of machine learning that has exploded in popularity over the last five years, typically requires even more expertise to work effectively. Deep learning systems rely on layers of connected processing units to extract insights from data. Getting a successful output from a deep learning system requires users to adjust the weights between units in a technique that’s often more of an art than a science.

That means trying to use deep learning systems in a new space can be next to impossible if you don’t have a mathematical understanding of how they work.

“Whenever there are algorithms or datasets being used, the people who created those things are going to know how to use them the best because they understand things at a deeper level,” Havasi said. “If you run into a problem, you have to go under the hood and make changes, and the people who truly understand these things are always going to have an advantage.”

That advantage is a big reason why Myrto describes Hyperplane as a very “founder-centric” VC firm.

“In AI, you have to be very team-focused and vision-focused,” Myrto says. “The technical teams are absolutely crucial. You need to have a team that understands the technology in a way that others don’t. At the end of the day, that’s what we’re investing in, really outstanding engineers.”

If building successful AI companies requires intellectual capital, then Boston should feel pretty good about its prospects. In their 2015 pitch to bring General Electric to the area, Boston officials described the city as “the world’s most sustainable source of exceptional talent.’’

There are more than 50 colleges and universities in the greater Boston area. According to the state’s 2017 Budget and Policy Center report, Massachusetts has the highest percentage of workers holding bachelor’s degrees of any state in the country.

When it comes to AI, MIT is unquestionably one of the leading research entities in the world, but other schools in the area such as Harvard, Northeastern, Boston University, Tufts and UMass Amherst also have AI-related programs and research labs that have produced a host of intriguing spinoffs.

“Boston really has an incredible heritage of engineers that are focused on these heavy-lifting technologies,” Myrto said. “Boston has always been on the forefront of solving the biggest problems in the world with frontier technologies.”

An Improving Tech Ecosystem

All that brainpower provides only fleeting benefits to Boston, however, if entrepreneurs feel the need to relocate before applying their research and ideas to the private sector. Strong tech ecosystems also require ample support structures for entrepreneurs, and it’s recent improvements in that area in particular that have people bullish on Boston’s future.

Habib Haddad, the president and managing director of MIT’s new investment group the E14 Fund, is one of those people. Haddad said as recently as five or ten years ago, there were several factors that made places like New York and San Francisco more appealing to entrepreneurs than Boston, and they had nothing to do with the demoralizing effects of the snow.

“Great companies like Facebook and Dropbox moved quickly to the other coast because some key elements just weren’t here,” said Haddad. “Now city officials, the startup community, investors, and universities are all saying, ‘We’re not going to miss out on the AI revolution the way we missed out on the consumer revolution.’”

There’s an old-fashioned mindset that academic research should focus on long-term, fundamental breakthroughs at the expense of more commercially applicable advances. In the past, that kind of thinking was certainly more pervasive in Cambridge than in Palo Alto.

Now the proliferation of university-based incubators in Boston is sending a clear message that schools support entrepreneurship. The emergence of university-linked venture capital funds such as UMass Amherst’s Maroon Venture Partners Fund, Boston College’s SSP Venture Partners, and MIT’s E14 Fund further blur the lines between the education and business sectors.

The number of accelerators in the city has also grown over the last ten years, led by groups like Techstars, which has helped local companies raise more than $750 million since it came to Boston, and MassChallenge, which has supported more than 1,200 companies since it launched with money from local officials in 2010.

And many research labs in the area now have corporate partnerships that allow researchers to consider real-world problems instead of the high-level work encouraged by more traditional funding sources like the National Science Foundation. Those partnerships offer a huge advantage in overcoming two of the biggest hurdles of starting an AI company: Determining product-market fit and securing access to large amounts of data.

“With AI, you see people building really cool technologies without identifying a problem, so they’re always trying to find a beachhead,” Myrto said. “But the research labs are interacting way more with investors, and that shift has happened in the last three to five years. They’re interested in building companies from this research. So we’ve seen a shift in mindset, and it’s accelerating big time now.”

Tech Giants Take Notice

One way of looking at this shift is that Boston universities are finally opening their doors to the private sector. The other way to interpret it is that the private sector finally beat their doors down.

GE’s decision to move its world headquarters to the Seaport District is just the latest example of an industrial giant establishing a connection to the city. All around Boston, companies are competing to gain access to the city’s cutting-edge research and talent pool, often elbowing out space for themselves in the process.

This summer Amazon announced a new office along Fort Port Channel, literally next to the space GE has claimed for its flashy new headquarters. Google and IBM have also expanded their local offices in the last three years. Other tech behemoths such as Facebook, Microsoft, and Twitter have made Kendall Square one of the most densely packed tech hubs in the country.

Many of these companies’ local branches are focused on AI. Amazon’s Cambridge office has been deeply involved with the company’s intelligent voice assistant Alexa. IBM has a local lab which seems to focus exclusively on AI, and last month the company announced a 10-year, $240 million investment in the new MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab.

“When you talk about industrial technologies and industrial AI, the race is ours to lose for sure,” Myrto said. “Soon that’ll spread to every industry. GE, Siemens already know this, that’s why they’ve been here. Boston’s background in industrial knowledge is really deep.”

These big companies are also competing for attention, forming partnerships with local tech groups, hosting events and creating their own events in an effort to position themselves as thought leaders. Such events give Boston’s growing tech community a way to keep its small-town feel and provide newcomers with a way to connect with peers over free drinks.

“We’re seeing enormous amounts of growth if you look at the number of events that are happening in Boston, especially around AI,” May said. “The support we’re getting is great.”

But partnerships and free drinks, of course, aren’t all it takes to be successful.

Follow the Money

CB Insights has tracked a rise in Boston VC funding over the last five years (and early 2017 results follow that trend), addressing a weakness that had major implications for area startups in the past. If advances in AI methodologies and computational resources had aligned fifteen years ago, Boston entrepreneurs looking to start companies would’ve had a much more difficult time than today.

Havasi, for instance, said Luminoso had some trouble securing seed funding in Boston in 2010.

“There were certainly funding gaps,” Havasi said. “There wasn’t as much early-stage venture capital or AI venture capital in Boston when we started. That has changed tremendously both across the country and in Boston. Now there are a lot of funds that are very savvy about AI, and that’s fantastic.”

Indeed, when the folks at NextView Ventures sat down to update their excellent Hitchhiker's Guide to Boston Tech last year, they had a lot of additions to make to the investor section. AI companies seeking their first round of funding have been helped by a number of angel groups that have recently institutionalized, including Converge Venture Partners and Half Court Ventures, which May started with Todd Earwood last year.

Myrto said the founders of Hyperplane saw a gap in early-stage AI investing in the area when they launched their VC firm two years ago.

“We saw an opportunity with big data and machine learning in Boston seed investing,” Myrto said. “The thesis of Hyperplane from the very beginning was about machine intelligence and systems intelligence, and we believe Boston is one of the best places in the world to invest in enterprise systems intelligence.”

New firms in the area such as Pillar and Underscore.vc have invested in companies offering AI-driven solutions, with others such as Glasswing Ventures (founded in 2016) and Hyperplane (founded in 2015), focusing almost exclusively on AI.

The growing number of Boston VC firms comes as every firm scrambles to adopt an AI investing strategy. More established VC firms in the area including NextView Ventures, Boston Seed Capital, and Flybridge Capital Partners have also counted AI-driven local companies among their recent investments.

And, perhaps most importantly, we’re seeing investment strategies increasingly veer from the conservative reputation Boston earned in the past. May described west coast investors as more aggressive, helping companies raise large rounds in order to achieve heavy market share, then using their balance sheets as strategic weapons.

“There are pros and cons to that strategy, but it also leads to really big companies at the end of the day,” May said. “I think Boston VCs think less that way typically, and our culture always needs more people thinking big. But you’re seeing some companies raise a lot of money now, and there are some investors that are very west coast-minded.”

Boston’s shortcomings in this area have been talked about a lot. Often they’re referenced as a mistake not to be repeated. Boston investors heading new firms such as Pillar'sJaime Goldstein and Jeff Fagnan from Accomplice (which split from Atlas Venture a few years ago) are among those who have talked about the importance of building large, sustainable companies in the area.

Myrto, who describes Hyperplane as very “west coast-minded,” said he’s seen a change in investor mindsets as well.

“The new generation of venture capital is certainly more inclusive and risk-taking, and those two ingredients are important to having a sustainable ecosystem here,” Myrto said. “Being a little more aggressive in the way we look at technologies and a little more futuristic in the way we see the world is a key ingredient.”

Riding the AI Wave

The race to produce great AI companies has, of course, already begun. Haddad guesses we’re in the “second or third inning” of AI perforating every industry.

Boston has already seen many AI startups gain traction, in some cases helped by recent eye-popping funding rounds. In a three week stretch of March, for instance, DataRobot's predictive analytics platform helped it raise a $54 million Series C and Kensho's financial analysis software earned the company a $50 million Series B.

Big funding rounds are becoming increasingly common in the area. Boston startups are working to overcome some of the largest technical barriers holding AI back, and they’re attracting attention across a wide variety of industries in the process.

Examples of startups working to increase AI’s potential impact include Lightmatter and Forge.ai. Lightmatter is focused on using light, rather than electricity, to improve computational speed and efficiency for AI operations. Forge.ai helps businesses use unstructured data in machine learning systems.

Havasi’s Luminoso, meanwhile, uses AI to analyze customer feedback in 13 languages to give companies insights on product reviews, social media posts and more. May’s Talla integrates AI into office chat programs like Slack and Gchat to help employees automate repetitive processes within a company.

And a number of Boston AI startups are competing with the same tech giants that have recently set up shop in the city. Netra CEO Richard Lee says the company’s visual intelligence software is more accurate than Google in image recognition tasks in head-to-head tests. Newton-based Semantic Machines has raised more than $12 million to make a conversational AI that its website says will “enable people to communicate naturally with computers for the first time.” The Semantic team shares that goal with a number of companies building the next generation of smartphones and smart speakers.

Other Boston AI startups are just plain cool. Cogito uses AI and behavioral science to read people’s emotions in real time. Neurala's product, the Neurala Brain, uses neural network software that’s been designed to closely mimic the functioning of the brain. It was first used to increase the intelligence of NASA’s Mars rover.

Other Boston tech companies such as Localytics, dataxu and HubSpot also now leverage machine learning for core product offerings.

“With AI and machine learning, we’re still exploring where it’s going, but it’ll be everywhere,” Myrto said. “And it’s Boston’s race to lose because you can see all the ingredients are here, from the labs to the talent to even the government being more innovation focused. We’re very young and very hungry to make a big impact on the world. This could be a huge long-term benefit for Boston in general.”

Boston taking a leading role in AI’s implementation could also be good for humanity. Silicon Valley’s “move fast and break things” mindset poses little real danger in consumer tech, but the implications of further AI advancements require a much more thoughtful approach.

“You want to really change the world with AI,” Haddad explained. “Boston has been thinking about AI for a long time. If all you’re doing is optimizing for the short-term opportunity to make money, you’re looking too close to you. And if you’re stepping back and looking at the horizon, that’s also not good because the world needs faster change. Boston has really converged those two views. We’re looking at AI in terms of its impact on society, and those conversations don’t happen as much elsewhere.”

No one can predict exactly how far-reaching the AI wave will be or what companies will come to define it. All we can do is consider how prepared the city is to support the next generation of entrepreneurs seeking to make their mark on the world.

In that sense, Boston seems to be in good shape to welcome the next Minsky to town.

Zach Winn is a contributor to VentureFizz. Follow Zach on Twitter: @ZachinBoston.

Images courtesy of Henry Han, GE, Gensler, Harvard i-Lab, and CB Insights.